Author: blindingham

Location

Property Search

Seeing Double

Blindingham Hall

September 25th 1852

It would seem that I have more in common with the Cornbenches than I thought.

Having returned home last week under the distinct impression that they had pity for me, I could not shake from my head the need to explain our ‘situation’ further. Quite why their opinion of me should matter I do not fully understand, but I wandered the Hall all the next day composing a speech giving my reasons for housing Cook in her hour of need. Surely they would not expect me to abandon her for ever in that hellish place full of madmen? I had thought it courteous to tell them of our impending absence – were they really concerned that Cook was to stay at Blindingham? I had clearly not explained myself properly and determined that I should see them once more before we leave for London.

So this afternoon, after waving Josiah off as he set out for London to secure our rooms for the Winter, I called Jennet and asked him to drive me over to Lydiatt House again. I had a note with me to leave with their maid if they were not at home, but as we turned up their approach I could see them all playing croquet on their upper lawns. I must say, they do seem to like to spend all their time together in a group. I wondered whether they all sleep in a huge bed and take their baths in an oversized bathtub so that they need never be separated for a moment. As Jennet stilled the horse, Mrs Cornbench swept up to me in the same alarming manner she had greeted me with before.

“Oh, my dear Mrs Hatherwick, how lucky we are to see you again so soon! Do you play?” She offered me her mallet but I did not take it. I could not see how to maintain my dignity and aim for a hoop at the same time. I was invited in to take tea and the whole family settled round me as I drank it. Really, I am sure they must be attached to each other by fine cord.

“I am sure you must be wondering what this second visit is concerning, coming so soon as it does after the first,” I began.

“Delighted to see you my dear, couldn’t be soon enough!” said Mr Cornbench, beaming at me. “I was only saying to my wife this morning what a pleasure it was to have met you. We have made your husband’s acquaintance recently, too. He is quite a character, is he not? A memorable man, we thought.” They glanced at each other like naughty children in the schoolroom. I, of course, had no idea they knew Josiah or what he must have done to earn himself such a queer description.

I hardly knew how to continue, but I simply had to explain about poor Cook.

“Mr Hatherwick and I are conscientious employers, Mr Cornbench. We could no more watch a faithful servant suffer than we could pull out our own teeth,” I said.

“Of course you couldn’t, anyone can see you are the most caring of people,” answered he, with a slightly nervous laugh. They looked at each other and then back at me and both smiled as though I had told them a most amusing joke. It occurred to me that they might know more about lunacy than one would have imagined. That would explain why none of them was ever left alone, I suppose.

I told them about Cook’s illness as well as I could and they said they had heard talk in the village a year or so ago about Mrs Everdown finding her collapsed on the Green on more than one occasion. It seems she sometimes became unwell after visiting the ale-house to look for Jennet. This was disturbing news to me, since I had thought she was only ever taken ill at the Hall. And since I do not for one moment believe Jennet to be the sort of man who frequents ale-houses, I can think of no reason why she would expect him to be there. I should not be surprised to discover that the poor woman witnessed some abominable sights in there and was overcome with shock.

As I was digesting this new piece of information, Mrs Cornbench spoke gently to me.

“Mrs Hatherwick, please do not spend a moment of your time in London worrying about what is happening here. As I said before, we are more than happy to visit the Hall regularly to keep watch over your staff. It is no trouble at all to us to help ensure you have an enjoyable Winter. It would be a pleasure, wouldn’t it Arthur?” She touched my sleeve with her tiny little hands and smiled at her husband, again.

After a while I decided we had said enough about the matter. I thanked them for their kind offer and agreed that they would be allowed in whenever they chose to call. I promised to send them our address as soon as I knew it, in case they needed to contact me. Not that anything untoward would happen, they assured me.

As I went to leave the house I passed the open door of a room I assumed was Mr Cornbench’s study. He has an Indian Tea-chest exactly like the one Papa gave me! I did not mention it – to do so would have been an admission that I had been looking too closely into a private room – but I was amazed to learn that there are two such chests in the County. I must mention Mr Cornbench’s name to Papa – perhaps they were travelling in the Indias at the same time – heavens, they may even know of each other! Papa may be able to confirm whether or not Mr Cornbench is as unhinged as he seems…..

Neighbourhood Watch

B’ham Hall September 16th 1852

I had occasion to visit our nearest neighbours yesterday. Mr Cornbench and his tiny wife have lived at Lydiatt House for a good few years now and have become established in the village almost as soundly as Josiah and I. They are a nice enough couple and she, despite being no bigger than a sparrow, has produced two strapping boys and a brace of girls. I do not warm to them, though, for reasons I can not fully express. However, being the next family after ours in importance, I felt I should apprise them of our plans to spend the Winter in Town, leaving a lunatic living in the Hall. I hesitated, of course, to refer to Cook in such terms directly, but I cannot pretend in this my journal that she is anything other. If she runs finally mad and burns the hall to its foundations, I feel it my duty to have warned the Cornbenches in case they wonder what the distant fires might be…

Jennet drove me over to Lydiatt – it is too far to walk even though it can be clearly seen from the belltower here – and I found the whole family at dinner together. Mr Cornbench was carving a fine bird and the children were singing some nursery song or rhyme to their mother. They do not stand on ceremony overmuch so the maid had shown me straight into the dining room with no announcement at all, like a physician in an emergency. The children broke off singing as I removed my cloak.

“My dear Mrs Hatherwick!” cried Mrs Cornbench as she swept towards me “How lovely to see you in our home. Please excuse our being at table.” She motioned one of the boys aside and I was welcomed to sit between him and his mother as if I had lived with them all my life. “Would you care for some guinea fowl, my dear?” said Mr Cornbench as he drew his knives together, “We have been saddened to hear of your situation, lately and have been wondering how we could be of assistance.”

I flushed as red as the cranberry sauce on the table. Villiers, or somebody, must have spoken freely about poor Cook and now we were the talk of the village!

“We are happy that our ‘situation’, as you put it, is proving to be of some helpfulness to those less fortunate than ourselves.” I answered. ‘How refreshing that you view it in that way!” said he, passing me a plate laden with the best cut of the bird.

Remembering the reason for my visit, I told them in the least alarming terms I could muster that they were now neighbours to a Hall peopled entirely by servants and half-wits (I include the Everdown girl in this, of course). Mrs Cornbench was not at all perturbed at the news and even offered to send her staff over daily to check that all is in order. She held my arm and assured me that Josiah and I must not give Blindingham a second thought while we are away. Her husband and sons all nodded their commitment to keeping a wary eye on my home.

I should be feeling happier to leave for London, I suppose, but I cannot help wondering why they seemed so keen to come to our aid. I do not want their servants wandering in the Hall every day. I shall tell Josiah of their offer and see if he thinks it a generous one. I do hope they are not simply in awe of us and planning to pretend to own the Hall in our absence.

Respite

Dearest Boo

Now that the cooler winds are upon us, I can feel us being pulled ever closer to London – I am beside myself in anticipation of seeing you all again! Josiah is planning to come up very soon to secure our rooms. I am hoping we can be in Brunswick Square again and I know Josiah is keen to be near his old associate – you know, the one we have allowed the Girl to work for over the Summer. I have been quite firm about not wishing that arrangement to continue and have insisted that her wages are not paid by us for as long as she is in his household. I had to warn Josiah that I should be taking advice from Papa if he did not accede to my wishes and he was horribly stern with me in retaliation, but he assured me the Girl’s income would be found from elsewhere and so I am satisfied. After all, the widower for whom she works cannot be in want of funds, living as he does at such a fine address.

Do you remember me telling you about the man from the village who had inspired Jennet with his talk of Chinese furniture, or some such notion? Well you would not recognise Blindingham now – it is practically stripped bare. Oh, it is such an improvement, Boo, you must be careful I do not call upon you to cast your belongings aside as well! Josiah has been most assiduous in his paring down operation and almost all the heavy things, which he says had been sucking the energy from us, are all gone – banished to the lumber rooms in the servants’ quarters, he says. It is a remarkably freeing experience to wander the rooms downstairs now. Instead of weaving my way carefully amongst the chairs and sideboards I can dance like a dervish from one doorway to the next! Really, I cannot recommend it enough.

In my excitement about coming back to London I quite forgot about poor Cook, whose mind is still unravelled I am sorry to report. I will not countenance bringing her with us – the bustle and noise would be too much for her fragile senses to bear – so I have left Josiah to decide whether to leave her in Mrs Everdown’s care or keep the Nurse on. I confess that I am so keen to relax my own duties where she is concerned that I do not much care which decision he makes.

So, we shall soon be Londoners together again.

Til October!

yrs

Effx

Clearance

I never cease to thank Our Lord that I am married to Josiah. Of late, he has taken to urging me to take more rest during the afternoons. He knows I am frequently drained by the constant attention I pay to Cook and he is becoming concerned for my health, the sweet angel. He is also assuming more household responsibility, I have noticed. Only yesterday, I came down from a most refreshing nap to find him overseeing the cleaning of the entrance hall. He had instructed the servants to remove all the furniture, the better to effect a thorough sweeping of the floors, and he was urging the undermaids to do their utmost to shine every surface in sight. I did not feel it my place to interfere – indeed I was glad to see him so involved in the domestic arrangements here. I have in the past been overwhelmed with the responsibility myself. I have been meaning to construct an inventory of furniture and ornaments for a good while but have simply not felt up to the task. So, if Josiah wishes to undertake such a duty I can do nothing but stand back and allow him his freedom.

This afternoon, as I wandered back through the entrance hall after completing my turn of duty with Cook, I was struck by the brightness and fresh welcome of the place. The dark stuffy pieces of furniture, most of which came with me from Hangerworth, have not returned to their place in the hall. Josiah will have found a hiding place for them all in one of the upper floors, I expect. In their stead are some delightful plants in pretty pots, which give one the distinct feeling that one might still be in the garden! How well he knows me and how much I love to feel the outdoors all around me. I do not miss the chairs, or the tables, or even that huge chest which Papa brought back with him from the Indias. I love the open greenery that has taken their place. That is why I thank the very Heavens for sending me Josiah!

Under Pressure

Blindingham Hall

August 26th 1852

This has been a monstrous day, the like of which I hope never to endure again!

I have been concerned that word of Cook’s fancy and aspect had got to the village – I have received some strange glances on my way around the place lately – and this afternoon I was proved tragically right.

As I walked with Cook in my small garden this afternoon, we thought we could hear whispering and laughter – at first I thought it must be Nurse since she has such an engaging nature and is often to be heard showing her amusement at Josiah’s instruction. Indeed I wish it had been them, for then the rest of the day’s dreadful events would not have taken place….

I looked up from helping Cook to sit on my iron reading seat and was truly shocked to see before me a gaggle of smudge-faced boys staring at us over the hedge. I knew them to be village boys at once – there is a certain physiological similarity about many of the children in Blindingham -there can be no questioning their parentage when so many of them clearly come from village stock. I moved towards Cook to protect her from view, but too late I realised they had seen more than enough. Emboldened by the dividing hedge, these boys began to jeer at poor Cook and some of them even threw small apples at her. She stood up and smiled at them, offering a sight gruesome enough to frighten even the hardest of ruffians, I should have thought. But at her stumbling approach, the boys grew more confident in their chanting and fruit tossing. So there she was walking unsteadily towards them and there they were, encouraging her with open disdain, which she appeared to take as confirmation of her status as Mistress of the hall. I was frozen with horror.

I called to the boys to desist and to go home before I reported them to their fathers, who would have been powerless to stop them I am sure. The boys were not surprisingly quite fearless at the thought of being chastised by such a collection of wastrels and redoubled their jeering at Cook and, now, at myself.

After a few more minutes of this I began shouting for the staff – they did not hear me at first, which is precisely why we were in that section of the gardens to begin with – and it was not until I shouted “Help, we are overrun with boys!” that salvation came in the form of Villiers who appeared, breathless in our midst. I have never been so pleased to see him, I do not mind confessing.

Villiers walked calmly towards the boys, who all stopped shouting and stared at him. He was silent for a while, looking at each boy in turn as if sizing him up for work, and then he said “Is there any one of you who wishes to come further into the garden and meet this fine lady, who has served The Hatherwicks royally and who is known fondly to your parents, even if you are not.” I was struck with admiration for his poise, and the boys themselves were open mouthed in awe of him. He paused for a mere moment and then whispered ” Now, which of you would like to come forward?”

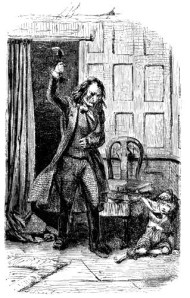

All but one of those urchins turned and fled.

Cook whimpered a little at their flight and started to ask me where her subjects had gone. I did my best to soothe her and help her back into the kitchen, hoping that this sorry and frightening episode was ended. I hoped too soon. The next thing I heard was a tiny, terrified voice pleading not to be hurt. I turned and saw the most alarming sight – Villiers was dragging the boy in through the window to the garden room, brandishing one of Josiah’s paperweights and bellowing that the boy was about to receive the hiding of his life! I concerned myself with making sure that Cook was safely returned to her rooms – interrupting Josiah and the Nurse as he was teaching her the appropriate way to arrange patient’s clothing should they become distressed whilst in her care. He is a very thorough employer, I must say, so he was irked at having to leave his instruction to go downstairs and deal with the situation. Nurse then helped me to get Cook into bed and I went directly to my dressing room to calm down.

I understood at dinner tonight that Josiah and Villiers have ensured that the boy, and probably his entire family and friends, will never return. I do not know exactly what they did and have no wish to be enlightened further. It is enough for me to know that I am protected by a brave servant and a commanding husband. That is more than I could wish for. I shall sleep soundly in my bed tonight and I trust the same can be said for Cook and for Villiers. The boy, I’ll wager, will not sleep soundly for some time.

Recipe for the Cook

Blindingham Hall

August 23rd 1852

Dear, Dear Boo

I am so weary of playing nursemaid! I have asked Josiah if he will let Villiers come with me to London – I am beside myself with the need to see you and LB, and Mrs Doughty and all my friends – but he says he cannot spare me from the Hall, not even for a day. I am not entirely sure what it is he needs me for, since he is hidden away in his office much of the day and overseeing the Nurse’s progress in the late afternoons. She is a very capable girl and I have told Josiah that I do not think she needs daily supervision, but he insists that Cook deserves only the finest of staff to attend her and that the Nurse is still in need of some training. He is a very conscientious man, my husband, Boo, as you know. So much so that he has asked me to consider keeping the Nurse on after Cook has recovered. He wishes to retain her services so that we may look after other unfortunates, should we ever encounter any. I am overcome with admiration at his thoughtfulness and shall agree to his request.

I walk with Cook in the afternoons now. She is robust enough to withstand a stroll in my little garden, which is by far the best place since it is not overlooked and we can be sure no staff can watch us. No-one approaching from the village would ever see her, thank goodness, because she does present an alarming vision to someone unused to her condition. She has begun to fancy herself as Mistress of the Hall and is wont to give me instructions as I walk with her! I do not correct this delusion – indeed it can be quite amusing – but I do not carry out her orders, of course. She does not notice my insubordination, poor woman, and I have no wish to distress her further by asserting my true position.

My concern is with her appearance, Boo, really you should see her. Nurse gave her some clothes belonging to Josiah’s Mama – who has been dead for fifteen years – and dresses her hair each morning in a variety of mountainous arrangements which make her feel quite the fashionable lady. Nurse then allows Cook to wander around the rooms she is occupying as if she were in charge. Her delusion, which gives her a frighteningly haughty demeanour, is thus fuelled by our actions. I do wonder whether this is the best course of treatment for the poor soul, but Josiah assures me that he and Nurse have drawn up a plan which requires us to pander to her fantasies for a while longer. I am tiring of it and should love to see you, as I say, but I fear that cannot be.

This has been the longest Summer in memory. Josiah is already talking about our Winter in London – I simply can not wait!

Yrs

Effie x

Direct Speech

Blindingham Hall

August 8th 1852

While I wrote to Boo earlier today, I told her I wished to find a new avenue of employment for Josiah. The very act of writing has made me think. I am so fond of Boo and so familiar with her that I feel shy using formal letters to communicate with her. Sometimes I wonder how it would be if I could be in instant contact with her even though she is so far away. I attended a lecture in the Village last month on the Wonders of Modern Science. I would not normally attend such a dreary sounding event but I wished my presence to be noted by certain persons I knew would be there. Luckily I did manage to spend a good deal of the lecture catching the eye of some people of influence in village matters. The lecture dealt with findings of a Mr Faraday and others whose names I cannot now recall. Mr Faraday has apparently spent twenty years – goodness me – working on something I did not grasp but which made me think of an idea. I dreamt of distant speech. How lovely it would be if I could be in touch with Boo, or anyone else for that matter, without the necessity of a boy, a postbag and a horse? What if there were a machine that could allow me to speak to her direct?

I shall speak to Josiah at breakfast and ask him if he could put his entrepreneurial mind to such a marvel!